Gear Up

Gear is one topic that every hiker has in common with every other hiker, but the gear you see on the Appalachian Trail today is radically different from what hikers carried in the past.

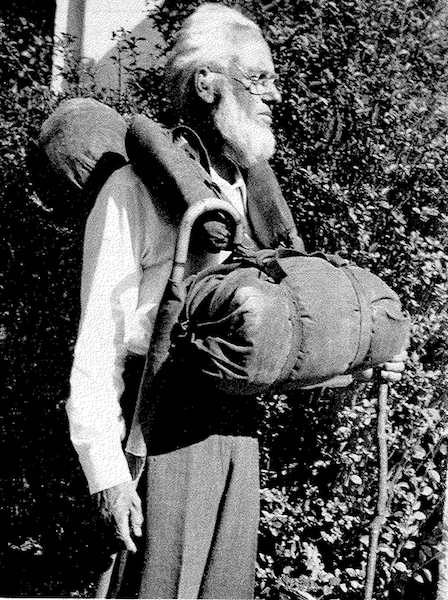

George Miller and his backpack, 03-01-1953. Potomac Appalachian Trail Club Bulletin, XXII. January-March, 1953.

Further Reading:

Earthtone, “How Backpacking gear has changed through the decades” The Trek.co (2017) https://thetrek.co/appalachian-trail/backpacking-gear-changes-through-decades/

Ross Millar, “A short history of sleeping bags” Wilderness Magazine (2011) https://www.wildernessmag.co.nz/short-history-sleeping-bags/

MILLS KELLY: If two Appalachian Trail hikers meet at a trail shelter, what are they most likely to talk about? Definitely food, especially food they’re craving. And gear. What tent are you using? How do you like that pack? Did your rain gear hold up in the storm this afternoon?

KELLY: Regardless of their background, their age, or how long they plan to be on the trail, gear is one topic that every hiker has in common with every other hiker. But the gear you see on the AT today is radically different from what hikers carried in the 1930s, the 1950s, or even the 1970s. How did we get from a world where hikers used to try to get their pack weight down under 50 pounds, to today where under 30 pounds is the goal?

[Music]

KELLY: Hello and welcome to Season Two of The Green Tunnel, a podcast about the history of the Appalachian Trail. My name is Mills Kelly and I’m your host. Eleanor Magness produced today’s episode.

[Music]

KELLY: Before we begin season two of our show, I want to say something to all of our listeners out there. If you’ve spent any time on the AT you know that there are two distinctly different ways to pronounce the name of the trail. Some folks say Appalatchian, while others say Appalaychain. Both are correct and how you say it depends on where you’re from. I’m originally from Southwestern Virginia where it is most definitely pronounced Appalatchian. But I’ve lived most of my life in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., where folks say Appalaychian. You’ll hear both versions throughout the show depending on who we’re talking to and I hope you won’t take offense if I or someone else pronounces in a way you don’t prefer. Now, on with the show!

[Intro Music]

KELLY: Let’s face it. Hikers do love their gear. And almost all of us know or have known at least one hiker – I’m not naming any names here – who loves their gear just a little too much. If you do know one of those hikers, you’ve had to listen in sometimes mind-numbing detail as they tell you why their tent, stove, boots, hammock, or pack is just the best thing ever. And by implication why their piece of gear is better than whatever you’re carrying. I’ve been on the receiving end of more than one of those gear lectures over my 50 years of hiking on the AT. I like to think I haven’t subjected others to lectures about my own gear.

KELLY: As annoying or amusing as those lectures can be, they all have one thing in common. They’re almost always about the present – why this tent, this stove, these boots are the very best thing anyone could possibly own. Right now. Today.

KELLY: But that relentless focus on the present makes it all too easy to lose track of the past. The history of our gear tells us a lot about the history of hiking and backpacking, of who hiked and why, and how technological change, business opportunities, and hiker culture all came together to help create the hiking and backpacking world we live in today.

ALBERT RILEY: My name is Al, I haven't got a trail name yet. And I'm from London in the UK.

RILEY: “Oh, favorite bit my gear. I'd say my hammock. There is a lot of hassle that comes along with it you really got to be committed to actually having that system and all the drawbacks it has to really love the advantages as well.”

KELLY: The gear hikers like Al carry today is very, very different from what the earliest AT hikers slung on their back or put on their feet. That old gear was heavy. As in really heavy. It wasn’t at all uncommon for a backpacker to head off onto the trail carrying as much as 50 pounds on their back.

KELLY: These days we’d think someone carrying that much weight was nuts, but in the 1920s, the 1930s, or even in the 1960s, hauling 45 to 50 pounds up a mountain was typical. One problem was that the modern backpacking store hadn’t been invented yet and so hikers had to rely on gear they bought at military surplus stores – gear made for soldiers by people who didn’t worry very much about how much that gear weighed. Or maybe a hiker had a catalog from one of the few outfitters that carried hiking and backpacking gear. They placed an order by mail or by phone, and then waited sometimes weeks for their order to arrive. And, of course, they had to hope the boots or pack fit them.

MORGAN SOMMERVILLE: I'm Morgan Somerville I'm currently the director of visitor use management. My connection with the AT goes way back though before working for ATC. Where I started in 1983, I was a backcountry ranger in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and worked on the AT portion of their backcountry management plan. And then I thru-hiked in 1977 or most of one and then prior to that did a lot of hikes on the AT and various other places.

SOMMERVILLE: My first backpacking trip was in 1961 when I was eight years old. We used cotton sleeping bags and number 10 cans and plastic tarps. The cotton sleeping bag was rolled up lengthwise and tied into a horseshoe shape and just carried over the shoulder. I don’t think I even had a backpack.

SOMMERVILLE: A good sleeping bag back then weighed maybe four, four and a half pounds. You know my good sleeping bag now weighs about half that. I had a state-of-the-art Mountain tent from North Face that weighed close to 10 pounds my current backpacking tent weighs like two and a half pounds, or something like that. So things have changed a significant amount over time

KELLY: Because good gear was hard to come by before the 1970s, some hikers just made their own equipment. Perhaps the most famous hiker who made her own gear was the legendary Emma Gatewood, who almost everyone knows as Grandma Gatewood.

EMMA GATEWOOD: I was 67 when I started the thing in 55. And then I was 77 when I hiked the last 500 miles on it in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine.

GATEWOOD: I had a blanket the first time. The last 500 miles I didn't have any blankets. I didn't have a sleeping bag, tent. I didn't carry cooking utensils and I didn't wear leather shoes. I wore Keds. One fella said, “Grandma, he said you did everything wrong but you made it just the same.”

KELLY: Yes, that was Grandma Gatewood in the last known interview she gave in 1973, just before she died. Instead of a backpack, she carried her gear in a homemade denim sack that she would hoist over her shoulder. In addition to what she mentioned in the interview, Gatewood carried a cup, a canteen, a baby bottle, a small pot, a spoon, a swiss army knife, a first aid kit, pins, a flashlight, a piece of rope, a raincoat, a warm coat, and a change of clothes. And if you want to see her Keds, which were really Converse hightops, a pair is on display at the Appalachian Trail Museum in Pine Grove Furnace, Pennsylvania.

KELLY: Grandma Gatewood wasn’t the only early long-distance hiker to improvise when it came to gear.

KELLY: George Miller, who thru-hiked the trail in 1953–two years before Grandma Gatewood–carried a homemade pack with a design that would be considered unorthodox. Actually, unorthodox is maybe being too polite. Miller’s rig was just plain weird. Hikers usually carry their load on their back, but that didn’t make sense to Miller. Instead, he decided that it made more sense to spread his load over many different areas of his body. We have a picture of his rig, which you really couldn’t call a backpack, in the show notes. When you take a look, you’ll see that his gear resided on his back, his chest, his stomach, his shoulders, and his hips. Folks at the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club were so intrigued by Miller’s design that they featured him and his rig in their quarterly journal. The story on Miller said, in part:

VOICE ACTOR ALISON LANGFORD: The purpose of the design is to carry about half the load in the front (on the chest) and half behind (on the back). The pack is made of water repellant canvas of medium weight and is put on or off over the head of the wearer. There are four parts:

A cylinder which opens and closes with a zipper fastener.

A section which can be opened flat and serves as a ground cloth for bedding. Bedding and clothing are filled up in this cloth and the ends closed by draw-strings to form a cylinder.

Two cylinders worn on each shoulder filled with clothing, and at times boxes or cans of food

KELLY: Despite wearing a pack that looked like some sort of human trap from a low-budget horror movie, Miller became the sixth person to successfully thru-hike the AT – at age 76 – so maybe he wasn’t so crazy after all.

[Music]

KELLY: Unlike George Miller, many hikers bought a lot of their gear at military surplus stores. Until after the Second World War one of the few national brand backpacks designed for the hiker instead of the soldier was the Trapper Nelson pack. Originally patented in 1922, the Trapper Nelson was an early version of an external frame pack and had a large canvas bag that was fastened onto two long wooden poles with long metal hooks. When they were wearing one, hikers looked like they had been strapped to a ladder and released into the wild.

KELLY: Empty, the Trapper Nelson is actually kind of comfortable. But it lacks a hip belt or any form of padding on the shoulder straps, so once fully loaded it was anything but comfortable. I know, because I recently donated one to the AT Museum and the staff and volunteers there had fun trying it on before it went off to the archives. Still, that wooden frame did force hikers to keep their back straight while hiking and was much lighter than anything available in a surplus store. So the Trapper Nelson had a brief moment of popularity among hikers.

[Music]

KELLY: Women had it even worse when it came to packs. When our producer Eleanor Magness and I visited the Appalachian Trail Museum earlier this year, we spoke with museum volunteers Sandy Moyer and Jerry Johnson about their experience hiking the trail before packs designed for women were invented. We were in the museum’s storage unit that day looking at some old gear they have in their collection and Sandy and Jerry got a good laugh remembering some of those old uncomfortable packs. Larry Luxenberg, the Museum’s president and founder chimed in during our chat.

SANDY MOYER: We had Keltys which were the very first made for women.

KELLY: Can you just talk about that for just a second about the fact that packs were made for men and women had to wear them?

MOYER: Yep, that's it. [Laughter]

JERRY JOHNSON: Well, they were, they were too long and they were too high. But the women's the women's had a different just had a different curvature. Yeah.

LARRY LUXENBERG: But they didn't even have hiking boots for women until…

JOHNSON: No, my first boots were Sears work boots.

LUXENBERG: That were for men.

JOHNSON: For boys. Yeah.

LUXENBERG: So would have been sometime in the 80s before they really started making stuff for women.

MOYER: Yeah, that's exactly right.

JOHNSON: Late 80s. Yeah

KELLY: And then in the 1970s, a new wave of external frame packs appeared on the scene, some designed for men, some designed for women, making it much easier for anyone to load up for the weekend or a week or more and hit the trail. Those new and improved packs were also external frame designs, but were much, much lighter, had pockets for your stuff, and even a brain.

KELLY: Here is Julie Queen, the manager of the Appalachian Trail Museum.

JULIE QUEEN: The brain is the part of the backpack that sort of flops over the opening, has storage space. You store your things in there that you want be able to get quickly. So snacks for the day, or maybe your first aid kit or your trowel, phone, sunscreen, that sort of stuff. Some hikers choose to take the brain off to reduce weight. Some people like to keep it on. It’s Usually the only part of the backpack that has small storage space.

KELLY: Personally, I prefer a brain because I hate feeling like the Scarecrow in the Wizard of Oz and because I keep my rain gear and blister repair kit in the brain of my pack. Both are items I generally need quickly when I need them, so having them right there on top of the pack just works for me.

KELLY: Packs aren’t the only gear to come a long way since the founding of the trail. Strider was one of the hikers we spoke with this summer.

STRIDER: I really liked my tent it's like a little home on the trail when you have a long day and you can climb in there and it's like your space and you can just throw everything out and it's comfortable and protects you from the bugs and the rain.

[Music]

KELLY: From the 1920s until the 1960s most hikers planning to spend the night on the trail carried either a military-style pup tent, or just a tarp of some sort that they could string up between two trees. Those old pup tents weren’t popular because they were light, because they weren’t. They were small and easy to set up. So at least they were convenient. And by the late 1960s they even had mosquito netting and a floor.

KELLY: It wasn’t until we started working on this episode that I really wondered about the name. It turns out that the pup tent first came into general use during the American Civil War and apparently, soldiers called it the pup tent because it wasn’t fit for a dog, much less a man.

KELLY: Somehow, between 1865 and 1965, pup tent makers hadn’t figured out that a tent with a floor was better than a tent without one. To keep the rain out, AT hikers had to dig trenches around their tents to keep the rain from flooding in around their sleeping bags. Of course, digging a trench meant carrying a small shovel. Not a trowel. A shovel. Who did that? Well, me, for one, when I first started hiking on the AT in the early 1970s. It wasn’t a big shovel and it folded up. But it weighed at least two or three pounds.

KELLY: Those old canvas tents weren’t naturally waterproof either. They had to be waterproofed by melting paraffin and rubbing it into the fabric. And a paraffin treatment only lasted a few rain storms, so hikers had to re-waterproof regularly just to stay dry.

KELLY: All that pup tent misery changed in the 1970s when tent makers like Eureka and JanSport introduced the hiking world to the joys of nylon tents. My first nylon tent was a Eureka and it had a floor, which qualified as luxurious in 1971. But it didn’t have mosquito netting, so my first nights on the AT were not bug-free.

KELLY: And then there was the tube tent. Here’s Morgan Somerville again.

SOMERVILLE: Well, it was fairly heavy plastic. I'm just guessing here is probably ten mill and the ones I remember were all fluorescent orange they were tubes of plastic that were about eight feet long perhaps and you were supposed to use things like pebbles or you know, maybe a walnut or something like that or an acorn to tie your rope and three different places on the end. And you had to use a stick to hold you know one corner up, and you know they were efficient they're light they're great. They did not breathe at all, so that you always have lots of condensation in them, and if you weren't on a perfectly flat place you tended to slide out over time because they were so slippery, but there were sort of like a large heavy duty trash bag without a bottom in it.

KELLY: My third tent was one of those bright orange tubes. Buying it was probably my first foray into trying to get my pack weight down, because it was so much lighter than my pup tent or my Eureka. To be honest, I hated it and ended up giving it to a friend of mine. Not only did I keep sliding out, but, it did not breathe at all and so I woke up every morning damp from the condensation inside. Clearly, I wasn’t the only one who hated my tube tent, because you still see nylon tents on the AT but I can’t remember the last time I saw a tube tent.

KELLY: In addition to breathability, nylon tents were much lighter than their canvas predecessors. Around the same time, sleeping bag manufacturers started using nylon and lighter weight fill material and so bag weights dropped just as dramatically. All of a sudden it was much easier for less hardy hikers to fill a backpack and head into the mountains, opening up the trail to many more hikers.

KELLY: Changes in how hikers cooked were possibly even more dramatic than changes with tent technology. I think it’s fair to say that most campers prefer a hot meal to a cold one, especially at night. Or, if they’re like me, they just have to have at least one cup of hot coffee to start their day. Before the Second World War, cooking on the trail meant building a fire. Which meant carrying an ax or a hatchet to chop wood for that fire. And matches that had to be kept dry. Or you had to be really good with flint and steel.

KELLY: The archives are full of photos of AT hikers in the 1930s and 1940s carrying some sort of ax or hatchet clipped to their belt. When’s the last time you saw that on the trail?

KELLY: Having to build a fire just to cook was a deterrent for many potential AT hikers. Fire building isn’t rocket science, but it can be pretty challenging in the rain, when it’s windy, or if there isn’t any dry wood nearby. Fortunately for hikers, during the Second World War, the military developed a number of small, lightweight backpacking stoves.

[camping stove lighting noise]

KELLY: Those new stoves meant hikers no longer had to build a campfire to have a hot meal. And they could cook in less than perfect conditions because wet kindling was no longer an issue.

KELLY: Those old camping stoves still had a few interesting designs. At the AT Museum, our producer Eleanor and I had a look at some of their old backpacking stoves with the museum’s staff and volunteers. We pulled out some of the old stoves from their storage unit and in at least one case we were all a little perplexed by what we were looking at. Larry Luxenberg was the first to try to figure out how it worked.

LUXENBERG: This stove I'm not sure what it is. It's pretty, pretty complicated. And it's got a fan here. I haven't seen one like this.

ELEANOR MAGNESS: It looks like in high school when they'd have you build those circuits.

JULIE QUEEN: It looks like there's a way to hook fuel up to it. It almost seems like maybe you would build a small fire in here and the battery-operated fan would keep it going.

KELLY: That could be because if you look inside their little ports, right. And I think you're right, I think you've built a fire inside the stove, and then the fan kept the fire going.

LUXENBERG: I've seen stoves where you build like a fire with twigs and stuff inside, but not with a fan like that.

KELLY: A stove with a battery-operated fan. What will they think of next? [Laughter]

KELLY: As you can tell from our conversations about backpacks and stoves, the AT Museum has some pretty cool stuff in its collection. If you haven’t visited the museum already, it’s really worth a trip to Pine Grove Furnace, Pennsylvania, just a short distance north of the halfway point of the AT.

[MUSIC]

KELLY: While we were working on this episode, Eleanor and our executive producer Jeanette Patrick decided to turn the tables on me. Instead of asking me to interview people like Larry and Julie, they decided that I had to move to the other side of the microphone and tell them about some of my own retro gear. The first thing I showed them was my SVEA 123, a white gas stove that I bought in 1974 and still use sometimes when I’m out on the Appalachian Trail.

[KELLY] “To light it requires a certain amount of conflagration. Because what you do is have to turn it so that the church key is attached. You take this, you do not attach the church key to the valve when you're initially lighting it. That's a rookie mistake. Instead, you take some of the white gas and you pour it over the top of the stove. There's actually a little receptacle at the bottom of the post that the gas comes up through. And you get a little in this, this little dish on top. And then you light that, and so you have flames that are like two feet in the air. And as that burns down, it heats the gas receptacle at the bottom and it heats the post that the fumes are coming up through. And once that's heated sufficiently, then you attach the church key because if you attach the church key before the church key is so hot, you can't touch it, because it's been burning with the gas. So once the gas is burned away from where the church key goes, and you attach the church key, and you turn it and convection has been created by the heat. And so you hear it roaring. And before you know it, there's a nice little roaring flame there. And it will boil water really fast. Not quite as fast as my jet boil, but really fast.

JEANETTE PATRICK: As someone who has played with a lot of fires, not especially safely, this seems incredibly dangerous.

KELLY: No, it's not dangerous at all.

PATRICK: Just you're just pouring gasoline on top

KELLY: You have to make sure that that the you know the tank is closed. But if you didn't close the tank, yes, it could cause a bigger conflagration in the woods. But honestly, the bigger problem with these is that the gas bottles, they because they have I'm not going to open it but it has a like a washer inside. And over time those washers fail. And they get hard. And if you don't remember to replace the washer on a regular basis, then it'll actually leak a little gas into your pack,

KELLY: Can you tell I love that stove? If you want to see what it looks like to light it, we have a video posted in the show notes.

[Music/nature sounds]

KELLY: All the new, lighter, and more convenient gear that began popping up in the 1970s had to find its way into the hands of AT hikers. As the popularity of hiking grew, a number of new outfitters began cropping up from one end of the trail to the other. Some were big stores like REI, that began migrating to the East Coast from out West. Others, like Appalachian Outfitters located just a few miles from our campus, were strictly local stores – the kind you see up and down the trail these days. Today’s small backpacking store carries a wide variety of gear from various national and regional brands, but Appalachian Outfitters actually designed, made, and sold their own stuff. And I oughta know. I spent pretty much every available nickel I had in that store when I was young.

KELLY: The upside to this retail explosion was that thousands and later tens of thousands of hikers could buy what they needed close to home or through a growing number of catalogs. The downside was that this new gear was expensive stuff. Many hikers couldn’t afford the new, lighter gear and had to settle for heavier gear. Before long it could feel like there were two kinds of AT hikers out on the trail – Those who could afford the good stuff and those who couldn’t.

KELLY: Still, even the less expensive gear was better than what the early AT hikers carried. As I already mentioned, those early hikers often hit the trail with 40 or 50 pounds on their back. Even with the less expensive and heavier gear, by the early 1980s most hikers were getting their pack weights down well under 40 pounds. Lighter packs meant more hikers could share in the fun on the Appalachian Trail. And that better gear also meant that hikers with little to no backwoods skills could establish a relationship with nature. They had camping stoves so they didn’t have to build a fire. Their tents were waterproof so they no longer needed a trenching tool. Packs had frames of metal with a hip belt to take pressure off their shoulders. In short, backpacking got a lot easier. Not easy. Just easier.

KELLY: What it didn’t get was a lot cheaper. While more companies making outdoor gear did have the effect of driving down prices for some gear, that gear was still expensive. For example, we looked at prices for 20 backpacks in a 1975 book devoted to gear reviews. The average price of those packs was $45, which doesn’t sound like much. But $45 in 1975 equates to $250 today. And in today’s dollars, the average price of a backpacking tent was $320. So a new tent and a backpack could set a hiker back almost $600.

KELLY: What that meant in the 1970s, and still means today, is that backpacking gear was and is an investment – an investment not everyone could or can afford. And when we think about who Benton MacKaye dreamed up the AT for - working class people from the cities - spending so much money just to go out on an overnight hike becomes a huge barrier.

KELLY: Despite the relatively high prices, advances in outdoor gear which made products lighter, opened up the backcountry to tens of thousands of new hikers. By the mid–1970s the Appalachian Trail was seeing a real boom in hikers. No one knows how many day hikers set foot on the trail in a given year, but we do know something about the people who hike it all. Between the founding of the trail in 1921 and 1969, only 59 hikers completed all 2,000 plus miles of the trail. But between 1970 and 1979, 793 people reported walking every step of the trail. And in the 1980s that number had jumped again to almost 1,500.

KELLY: We know the increase in day and weekend hikers was even more dramatic–we just don’t have exact numbers like we do with thru hikers. By the year 2000, the National Park Service estimated that more than two million people set foot on the AT every year and by 2020 that number had jumped to as many as four million.

KELLY: Gear makers like Kelty, Jansport, Eureka, SVEA, Coleman, Campmor, and more recently Big Agnes, Gossamer, JetBoil, MSR, and so many others have helped make backpacking accessible and fun. But at a cost. A trip to the surplus store might not cost you a week’s pay, but it will still add up. And there will always be the proverbial gear-head hiker who just has to have the absolute lightest and best gear. To have the very, very best of everything hikers can easily spend more than $1,500–sometimes lots more.

KELLY: There were so many other gear innovations we could have touched on in today’s episode – the invention of the battery-powered headlamp, sleeping pads, lightweight boots and shoes, maps on your phone, and more. But if we were going to pack in all of those changes, we’d have to spend another few hours. Instead, we decided to focus just on packs, tents, and stoves, largely because these three innovations were all critical to making the AT more accessible to the largest number of hikers. We’ve posted some suggested readings in the show notes at R 2 Studios.org if you want to know more about the history of some of these other gear items.

KELLY: That's it for today’s episode. We’re glad you’ve joined us for Season Two and we hope you’ll stick around for more episodes like this one. Thanks for listening and we’ll see you soon.

[Ending music]

—--

MAGNESS: The Green Tunnel is a production of R2 Studios, at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. Today’s episode was produced by me, Eleanor Magness. Our executive producer is Jeanette Patrick, and she also did the sound design for this episode. Our original music is performed by Scott Miller of Stanton, Virginia, and Andrew Small and Ashlee Watkins of Floyd, Virginia.

MAGNESS: A special thanks to Morgan Sommerville, Jerry Johnson, Sandy Moyer, Larry Luxenberg, and Julie Queen for appearing as guests on this episode. And to Alison Langford for reading the description of George Miller's pack.

MAGNESS: If you enjoyed this episode of The Green Tunnel please give us a five-star review wherever you listen to podcasts. Or follow us on Instagram at Green Tunnel Pod. To explore all of R2 Studios' podcasts, go to R 2 Studios.org

MAGNESS: Thanks for listening! And we’ll see you soon.

[Fade out outro music]

Julie Queen

Manager Appalachian Trail Museum

Julie Queen is the Manager of the Appalachian Trail Museum and has been in this role since March 2021. She thru-hiked the AT in 2016 and served as a Ridgerunner with the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club in 2017.

Larry Luxenberg

Founder & President Appalachian Trail Museum

Larry Luxenberg is the founder and president of the Appalachian Trail Museum in Pine Grove Furnace, PA.

Jerry Johnson

Jerry Johnson is a docent volunteer at the Appalachian Trail Museum. She helps with the Museum’s library and archival storage facility.

Sandra Moyer

Sandra Moyer is a volunteer at Appalachian Trail Museum She works as a docent, in the Museum’s library, and archives

Morgan Sommerville

Director Visitor Use Management

Morgan Sommerville is the Director of Visitor Use Management for the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and was a regional director of the Conservancy from 1983-2021. He completed most of a thru-hike of the trail in 1977.

https://appalachiantrail.org/

Al "$tache" Riley

Albert Riley is a 2022 thru-hiker from London, England.